Is the fact that a learner completes a prescribed set of training, sufficient evidence that they’ve accomplished what the course set out to teach them? In most instances, the answer to that question is: No, it is not! When designing test questions that demonstrate achieving “real” learning outcomes, L&D professionals must use evidence-informed tactics for question construction. They must also consider the context in which they’re administering the test, what evidence they need from their students to prove that they understood the material and if they can substantively demonstrate that understanding.

Use Evidence-based Tactics to Contextualize Your Questions

There has been considerable research to understand the impact of question construction and its implication on how learners respond to them. The adaptation of Response Modelling (RM) techniques, and Item Response Theory (IRT) to academia, has produced a vast body of statistical evidence for helping test question preparers measure test accuracy, and improve their (questions) reliability as predictors of learning outcomes. However, it’s important to deploy these strategies in the proper context.

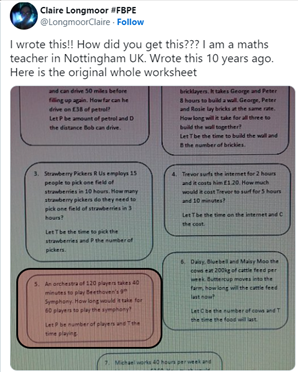

Some years ago a math teacher, Claire Longmoor from Nottingham, presented students with a multi-question test, where one of the questions generated substantial internet buzz:

The question went something like this: “An orchestra of 120 players takes 40 minutes to play Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. How long would it take for 60 players to play the symphony? Let P be the number of players, and T the time playing”. So, let’s put some context around the potential application of this type of questioning.

If this question is posed in the context of a Project Management course, the lecturer would likely give bonus points to anyone that justified the “project’ would take longer than 40-minutes to finish – seeing that larger teams are often more challenging to manage.

A lecturer of a course on classical music would be aghast if, after attending 10 modules of her course, a student responded with an answer of 60-minutes – by reasoning that it takes 120-players 3-minutes each (120/40 = 3), so, the addition of 20 more players could complete the symphony in 60-minutes less time (20 x 3)! Disregarding context (symphonies have set durations!), math-minded individuals might come up with an answer of 180-minutes (120/40 x 60 = 180).

When designing tests, one fundamental consideration, for writing better test questions to assess learning, is to use evidence-informed tactics to build your test banks. But, as you apply that evidence to your questions, remember that framing the question to also assess learning context is really important.

Strategies & Tactics that Work

The above symphony test is a perfect example of why context is important when designing test questions. It’s important for course designers to match test questions with learning objectives (i.e.: Was it meant to test knowledge about how symphonies work? Or was it a test about divisions, multiplications, or the team management?).

Your choice of the type of test must, therefore, be driven by the context of the subject matter being evaluated. A performance test would be better suited to show (demonstrate) what was learned, while an essay or narrative-type question is ideal to test whether the learner can explain what they’ve learned. And based on that context, you could assemble test questions containing multiple features, such as Multiple choice, True/False, Matching lists, Short answers, Essay responses, and Computational elements.

Here are four strategies and tactics to help you build evidence-informed test questions:

- Cognitive Complexity: Design questions that focus on intellectual achievements ranging from simple recall to critical thinking, and from complex problem solving to reasoning. Use the 6-level Bloom’s Taxonomy as your guide to developing your questions.

- Relevance: Stay away from including test questions that aren’t relevant to your course, or that don’t add meaning to a learner’s effort in answering them. A question is only as effective (in accomplishing its objectives) as a learner’s appreciation of it as a teaching aid.

- Scope and Quality of the Test: Developing test questions that are too broad in their scope, may prove deleterious in their impact. Focus on preparing questions that cover specific aspects of the course, so you can more easily assess skills gained, and knowledge transference as a result of the course.

- Questions Must Mimic Learning Content: The facts are clear: Test for new concepts, theories, or knowledge, not covered in a course, and learners will disengage from learning. This includes formulating tests using language that’s inconsistent with the course – such as using valid, but alien lexicon, short forms, acronyms, and abbreviations.

Dos and Don’ts: Question Construction Tips & Techniques

When building your question bank, the strategy you employ depends on the context and the type of questions you create. Here are some time-tested, proven Dos and Don’ts for some of the most popular question types:

- Multiple Choice (MC) Questions

- Avoid the use of long and complex statements. When possible, formulate questions as a single sentence. Research suggests a correlation between the length of an MC option and its correctness

- Stay away from using sentences that offer a clue to the correct answer

- Don’t use statements verbatim from the learning content. Paraphrase the question in your own words

- Provide alternate choices between three or four (no more than five). Research shows that fewer (three) options are preferable to more, and it also serves to improve the validity and reliability of the test

- Research[ii] indicates question-builder “middle bias” – so, place correct answers in all positions (first, middle, bottom, last)

- True/False (TF) and Multiple TF Questions

- Avoid ambiguous, negative, and double-negative statements when building your questions

- Make liberal use of MTF questions. Research shows that the use of MTF questions is more effective at providing insight into learners’ thinking

- Research indicates that test-takers often guess on the side of “T”, when uncertain about their responses, especially if they encountered the same/similar choices in prior questions. To account for that bias, keep the proportion of “F” responses slightly higher than “T” ones

- Free Response (FR) Questions

- When testing the depth of clarity of a learning concept, use FR questions. Researchers found that, while responses to FR questions often indicate a larger proportion of partially correct or unclear concepts, the answers do provide a more authentic picture of a learner’s thought process/profile

- Consider using FR questions in tandem with MC questions on related topics. Research corroborates the fact that FR questions can be approximated by MC equivalents. However, using both test question strategies simultaneously, may better aid in assessing learner understanding of different aspects of the same subject matter

- Matching Questions

- Adding the same choice multiple times, in the same question, can counter the effect of guesswork

- Order the matching sets logically – numerically, alphabetically, chronologically

- Avoid including implausible or impossible choices as part of your matching set

- Stay away from heterogeneous matching sets – e.g.: Dates combined with personalities. Use phrases or words that are similar (all dates, all country names, all inventions, all types of services/products) for learners to match

- Keep the responses list longer than the question list

- Make sure the complete question – instructions, questions, and matching sets, appear as a unified set on a single sheet (screen). Having test-takers turn over sheets, or switch screens, while assessing their answers and responding to the question, is an unnecessary distraction

Concluding Thoughts

In using the above research-supported test question-building strategies, testers must always maintain their focus on the context in which they are writing questions. While introducing “distractors” is fair game (and often encouraged!) as a testing strategy, test questions that lack context (or are introduced out of such context), may have a negative effect on the test taker. Instead of serving as a learning aid, the test might detract learners from achieving the stated learning objectives of the course.

If you’d like to learn how to design eLearning courses like a pro, sign up for the Instructional Design for ELearning program!

Leave a Reply